‘Painting is the highest form of hope.’ – Duncan Wylie

In the latest interview with Art Talk Magazine, Duncan Wylie discusses his practice, influences and plans for the year ahead.

Art Talk Magazine: Dear Duncan, thank you for your time, and the opportunity to do this interviewwith you. We always start by asking the artist what drew them to art, and what career they would have pursued if they had not become an artist.

Duncan Wylie: I grew up surrounded by art and books on art. From spending a lot of time at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, where my mother was the curator, to our shelves with books on Goya, Gaugin, Picasso, Cezanne and Rodin at home. If there was a drawing to do in class, since the age of 5 years old, I would be designated. Later I tried other things—architecture, photography, music—but there was no choice. Architecture is too slow, and photography is not very tactile. Painting and sculpture have an immediacy that is almost human. I need that.

ATM: The inspiration for your early work is very well documented in the essays on your website, which make reference to your early life in Zimbabwe, the dangers, the destruction, the fear for the loss of life and the destruction of your home. We live in a world today where conflicts, rather than abating, seem to be multiplying. Do you feel, like many people we speak with, that we are reaching a crescendo and that more peaceful times lie ahead once the storm has passed? Or are we, as humans, condemned to ever-repeating cycles?

DW: Difficult to say really: It seems we are in a time of "poly-crisis," where the environment seems to be on the verge of collapse, and now conflict on a major scale has become a constant news feed, all of which adds to a crescendo effect, as you say. I would love to say that this is the dying kick of a misguided patriarchy and that an new era of matriarchy will now lead to more peaceful and constructive symbiotic relations, led by mothers, not navel gazing, blinkered, and macho autocrats. Even if this were to happen though, the nature of power is to corrupt... so even with such juridical defenses of democracy as in the USA and the UK, we are and probably will witness the testing of these to the limit.

ATM: Much that is written about your art makes reference to you as a true artist and genius, able to illustrate the notion of multiverses (or is it parallel universes), to explosion and implosion, references to multitudes of scenarios borne from the same individual and situations. AI which is on everyone’s lips these days opens these variations even further. How do you feel about this Pandora’s box that has been opened, and can never be closed again?

DW: That use of the word genius was in a very philosophical text on my work by an Austrian philosopher - it was passable in context, otherwise it doesn’t sit well with me. Though I do seek to find what is hidden behind each image and the potential within each image or fragment of an image I use, to generate a relevant painted image that speaks about today. With AI, as you say, the genie is out the bottle on the creative side: fact and truth and individuality are all now under threat, but this is nothing new; growing up under a dictatorship with a secret service similar to that of East Germany before the fall of the wall, fact and truth and individuality were always under threat. In fact my early paintings from 1999-2005 treat this mistrust of the image, as if we have to double-guess what we see... Now it seems this phenomenon will be present in even the most progressive societies. Through online information and AI the narrative can be completely controlled and manipulated, as in the former East Germany. Defenders of truth and individuality have their work cut out once again. On the scientific side, and on a positive note, if AI and deep learning can produce algorithms and solutions in 5 years that would otherwise have taken 50 years, maybe that can help find a faster way forward on, say, climate change.

ATM: I was looking at the artworks featured in your exhibition at the Backslash gallery, and I smiled at the "double entendres” of some of the titles such as “whistleblower”, with paintings showing African figures blowing a whistle while the first thought that came to mind was individuals who attract attention to facts and events which uncover bad actors or actions. What was your intention when you created these paintings?

DW: For me, whistleblowers are some of the most important people in society and are often overlooked. They risk their skin to speak out, often from a position of anonymity. They risk their career, family, home, and even their lives to speak up against corrupt or abusive people and systems. My paintings are made with respect for their integrity, or outspokenness, and also because of the similarity of their stance with that of good artists; often you need to risk and sacrifice things to do valuable work. The paintings are also portraits, but the story is ‘hors cadre'—out of the picture frame—and is also an alarm bell about concerns such as climate change - Arctic Whistleblower, 2022 - painted in glacial blue, and - Whistleblower (orange), 2023 - obviously the chromatic opposite, painted in hot, bright orange. Also, in the history of art, no one has painted Whistleblowers.

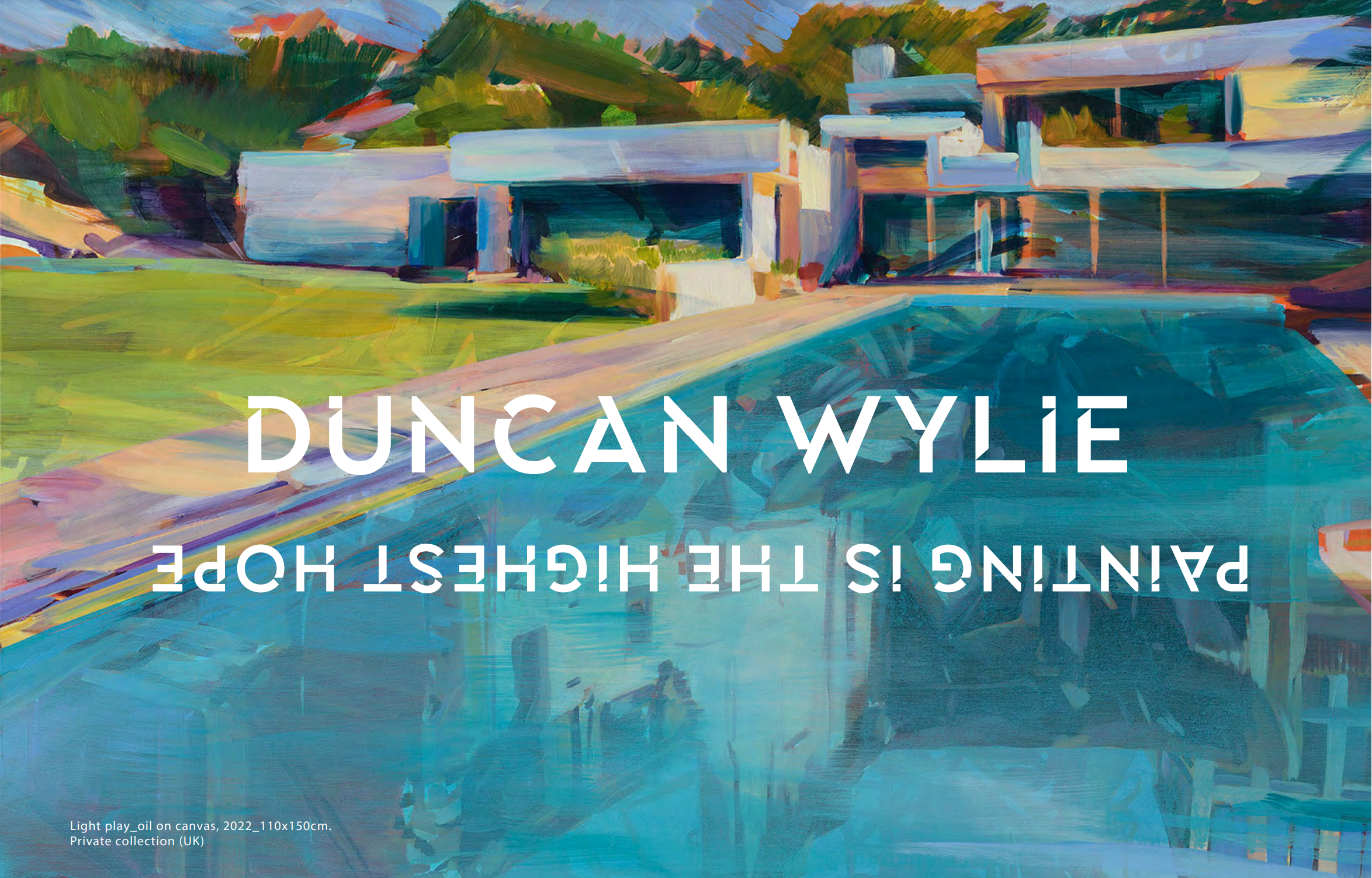

ATM: “Volume and surface”, a very architectural painting that is pleasing to the eye; a beautiful modern villa with a pool in front. And yet, after looking at your other paintings and reading the essays, I feel that I’m missing something, that there is a deeper meaning hidden beneath the surface. What is it that I’m supposed to see that you wanted me to see?

DW: This painting and others in the series are based on the idea of a false reflection; there is literally a false reflection built into the pool of the painting. The modern/constructivist villa is in fact painted over a painting of a demolition turned upside down, and this is what creates the false reflection. The slight turbulence/movement in the pool is in fact created by the vigorous painted marks which make up the upside-down ruin, and create and underline the sense of floatation in the water. The contrast between the super-luxurious villa and the reflected ruin is the crux of the painting, referring to the transparencies of Watteau in his “fêtes galantes”, a sort of transcendental “fin d'époque." As for me, one can no longer paint the idylllic, hedonistic pools of, say, Los Angeles (David Hockney, Ed Rucha) in the same way; water is now a scarce resource. It is also a reflection on the structures we have created and whether they can still function in the same manner. The pools in Zimbabwe are literally cracked, so these nostalgic images of late afternoon swims and pool parties are now lost in time. Or one can’t enjoy them in the same way if one has any sort of political/ social conscience regarding the general situation of the country, idem in parts of the world where water is now scarce. The use of the modernist constructivist villa in the background to solve this pool series was important for me, as it was systematically the necessary element to contrast the energy and colour of the painted upside-down ruin. I painted several of these compositions until I understood that this elongated villa was in fact a memory of the elongated and constructivist museum built on the Zimbabwean soil: the National Gallery of Zimbabwe, where I grew up and where all Zimbabwean artists aspire to show. It is a beacon of hope in a way, accompanying all Zimbabwean artists on their journey. Also, the title Volume and surface is very deliberate: water has this inherent contradiction - it is all surface, but hides huge volume. Paintings are made through this paradox: a volume of feeling and meaning, compacted onto a 2D surface. That is the challenge, in any case, for a good painting.

ATM: “Sans Titre (Mobile Home)” from 2012 is very reminiscent of the type of vessels that immigrants would use, put together, to cross waters to a better life. Is this painting a reference to a mobile home in the context of no home that many immigrants end up feeling they live with; a “better life” that they do not fit in, the discomfort of a new home?

DW: The Mobile Home series is about what happens when you lose your home, and the identity that you lose with it, which leads to a journey. After a catastrophic event, there is a quest to find a new place. Homes in Zimbabwe and around the world were under threat from 'tsunamis'—either man-made as in the operation Murambatsvina in Zimbabwe, or natural, or other phenomenon provoking large-scale migration. At this time, I also had to destroy my previous way of painting (or my identity in paint) and invent a new one, which is what I did with the bulldozer paintings: Gaza 1, Gaza 2, and Afterparty. After this, the rafts became synonymous with the journey of self-discovery, as I had to construct them as I was sailing them, so to speak. It became a leitmotif: the painter Chardin says, “Painting is an island of which I have only skirted the edges." The raft appeared periodically and literally as a life raft in my journey as a painter and as an “état des lieux,” or questioning of where I was at in paint. Had I put a foot on the island yet? Which bank was I on—had I left the raft or was I about to get on? Under this raft is a painted facade under demolition and turned upside down, once again to enhance the idea of floating, both in the image and when I physically paint it. It is actually one painting floating on another, with highlights of the hidden painting peeking through and affecting the final image, influencing how it progresses. The time of the journey is built into the raft, and it carries its own history.

ATM: “State House" (2010), “Cabin Fever”, 2009 and “After Party”, 2006 somehow came together in my mind. Despite the destruction in the first two paintings, I was left with a sense of optimism rather than one of anxiety, fear or desolation, as though the destruction led to a rebirth, to new buildings that would re- place the destroyed ones, the destruction was followed by an “After Party”. Your paintings are infused with a sense of inevitability and a sense of hope for the future. Is this my eternal optimism speaking? Why the rubble in your paintings?

DW: Painting is the highest form of hope; the works you mention represent different moments of an event: the instantaneous Afterparty, the during Cabin Fever, and State House which is a compilation of the before, during and after. Through the use of these broken fragments and moments of construction and deconstruction, I sought, as a painter, to re-construct my own gestural and colour vocabulary from the fragments and debris of actual events that affected me. They are painted with highly energised brushstrokes and colour that reboot the fragments. Thus, they are really constructions! I am creating my identity not from the history of the London School of painters, or the New York school of painters, but from trying to identify and mirror the entropic energy of the contemporary world in my actual painting, and the debris or rubble you talk about is residue or part of my pictorial process. I don’t seek to describe scenes: I multiply the use of fragments (like Rodin) to construct an “event”, literally a pictorial event where the action cre- ates the final image, balanced between abstract marks and observed reality: the debris has been created by the construction of the image through the layers of marks. The resulting images are not a representation of something, they are the actual result, or "event,” and contain the history of their own making.

ATM: The “Bee Sting Therapy” series from 2018 has the subtitle “(Gaza)”. Can you share the reference?

DW: The Bee Sting Therapy (Gaza) series is about colonies of people, of empire, of Facebook. Who controls who? Who manipulates our information. The ef- fect of the British Empire on the indigenous people of Zimbabwe. Of an Israeli tech company helping the authoritarian government of Zimbabwe ‘win’ elections through falsifying election data. Facebook and Cambridge Analytica have manipulated information in progressive nations elections. I used the anonymous masks of beekeepers (a sort of architectural suit) as symbolic of those who work in the shadows, manipulating the smaller players—the colonies of bees. This cluster of narratives seemed like an interesting point from which to make a painting dealing with these complex contemporary issues, while introducing more solid figures into my painting. The images used were of a group of beekeepers in Gaza who would also practice bee sting therapy: stinging themselves with their own bees for health reasons. I was'stinging' myself with paint, to make a stronger painting. Fueled by anger from the absurdity of the borders (bees don’t recognise borders) and frustration that a tech company is interfering with a people trying to free itself from the chains of 40 years of despotism for profit.

The Gaza reference is also a reference to my big stylistic change in painting, when the first bulldozer/landscape paintings ended my previous way of working, and generated a new identity. Painted with images of bulldozers in action during the retreat from Gaza by the Israelis in 2005, which served as substitutes for images of the operation Murambatsvina in Zimbabwe, images of which were impossible to obtain as there is no liberty of the press there. In the Bee Sting Therapy (Gaza) series, introducing the solid figures into my painting altered the space and the way I use paint in about the same way as a bulldozer knocks over a house.

ATM: “Self Construct” feels like an “autobiographical” series. From Zimbabwe to Paris, then London, you are often described, as is your art, as nomadic. Where do you feel home is? How have these different cities help “construct” who you are today and your art?

DW: Yes the Self Construct series “can be read as a painter’s self-portrait, a man painting in permanent gestation"—to cite Juliette Singer*—walking forward on the rail track, his body conflating with the landscape. I feel at home both in London and Paris, with Paris being my intellectual and very rooted adoptive home for 20 years, where I still keep a studio. London is more physical, diverse and closer to nature, being Europe’s greenest city (a fact not many people know) and where my family thrives in a wider and less populated space. Paris put me in proximity with the painters I had only seen on my book shelves in Zimbabwe and with an intellectual and cultural network that nourished my hunger for art. London is a new pictorial challenge as the environment is much more individualistic, and there are many, many painters. A painting that I started in Johannesburg, continued in Paris and finished in London called Multiple realities (Multiple Horizons), Johannesburg/London, 2016 was chosen for the inaugural contemporary exhibition of the Louvre Abu Dhabi. The show was called A Global Stage, and the painting entered their permanent collection. The fact that the work was a palimpsest of geographies and layers mirrored its global theme. So the plurality of my work in different cities has definitely helped construct who I am today.

*Juliette Singer

Chief heritage curator and director of contemporary art projects at the Petit Palais, Paris

ATM: 2024 is around the corner already! What are your plans for the year to come?

DW: Early in the year, I have a group show called La Seine at a very interesting and popular museum in Paris, the Carnavalet Museum, where a painting from 2003 will be shown. Very few people know my paintings from this era, which are very different from today's work and are very connected to Paris. I am also excited to work towards a large publication—a monograph compiling over 20 years of painting. I will also be hard at work on new paintings for a second solo show with Backslash Gallery in Paris.