Duncan Wylie in conversation with Guy Tosatto

Guy Tosatto: Can you describe how you work out your pictures? How you start them, and then what happens?

Actually my approach is bound up not just with how I work the paint itself, in a gestural and off-the-cuff way — this applies to the first small picture to come out of my stay in Israel when I saw the destruction of Gaza—but also with the visual effect of this picture, in which you can clearly see tiles falling from a bungalow roof. What is important in this first small picture is that you get the feeling of a chaos in mid-air, with those falling tiles being tossed down by the arm of a mechanical digger. When I painted that picture, first of all in a small format, then enlarging it to a two-by-three metre format, I actually understood that it wasn’t the snapshot notion that concerned me the most. A “more structured” chaos, or one that lasts over time and is at the same time instantaneous. At the time, though, it was very instinctive. I wasn’t able to conceptualize it. Needless to say, painting thirty-odd mechanical diggers didn’t make a lot of sense. What’s more, finding photos showing that precise moment was very hard. The next step was to find how to reproduce “that moment” in painting itself. It took me a while, and I painted lots of bulldozers, canvases that nobody’s ever seen, depicting a moment of impact, with a me- chanical digger, a bulldozer, or some other machine, but invariably with that notion of impact. And then one day I painted the interior of a dance room with a red convex roof. I didn’t carry that work through, but what interested me in it

was the empty space. A month or two later, after a stay in Sofia, in Bulgaria, I turned that picture upside down and I saw the structure of that interior quite differently, with lights hanging the wrong way round—upwards. There was a fine empty space with things floating about in it, and in that interior I painted a totally exploded exterior. The feeling I had when I did that was that the de- bris I was painting was floating on top of the initial image. So I rediscovered that moment when something is suspended, in mid-air... What also interests me is that this theme of exploded structures allows a mimetic connection between architectural features and brush strokes. All of a sudden there’s an indecisiveness between abstract sign and figurative form. That’s the second key, which brought me to where I am today: painting one image in another so that it floats in the first one. It’s possible to draw a parallel with Richter’s painted photographs where effects of paint are overlaid on an image.

This also takes us back to my works produced ten years back where, from a distance, the forms were very precise, like a photograph, whereas, close up, they were very painted, with a very assertive touch and an almost abstract rendering. That picture, which was called Paris, Sofia (Harare), because it was painted in Paris from pictures I’d taken in Sofia, while at the same time referring to what was going on in Zimbabwe, was significant because there was a very interesting notion of scale. By painting, within an interior, an a priori larger exterior, I reverse the ratios of scale between those two spaces; these

are pictorial games that only I’m aware of. This makes the approach a bit sur- realist, and I like this game when I paint. In the end, you don’t necessarily see the result, but this story is embedded in the work. It’s my way of incorporating things and working them, knowing that, at a given moment, in a year or two, they will appear differently. I’m very fond of Max Ernst and René Magritte, and that slightly unreal idea of floating, which you don’t see a priori, but which is there.

So when I say overlay of images, it’s wrong. It would be better to talk of embedded or dovetailed images.

No, both. In fact this system of overlaying and dovetailing enables me to paint all the chaos I want to, because it’s the pictorial process which gives rise to the chaos itself. This implies that I can use images of reality without having to reproduce them in a literal way. That type of reproduction doesn’t interest me, because then I’m describing them, and if I describe them, this means that the matter is dead. What’s important is that the process gives rise to chaos, and with it we find that notion of “something happening”. It’s neither the before nor the after: it’s really the during, the actual moment of pictorial choices. My images are highly constructed, constructed in stages, but the fate of an ove- rall image isn’t controlled by me at all. I may think: “Hey, this image is going to work really well on that one”. And then, at the end of the day, a third one can

crop up, just like that, without any warning. With Power Sharing, I thought that the right side of the picture was going to be completely covered. But the energy that’s there is perfect like that, with its very abstract look. All at once I have to push the left side, which is very photo-realist (without necessarily being that), to offset and give more reality to the abstract side. So there’s always an interplay of contrast between the real and the abstract, and this involves overlaying as much as it does dovetailing.

From the start you’ve been working on the theme of architecture. This is some- thing that permeates all your work. Could you say something about this?

Architecture, yes, was primordial insomuch as I’ve always tried to use spa- ce in painting. And the more space there is in painting, the more space there is for the eye to wander about in. For me, architecture was neces- sary for understanding the space in which we live and work. In Paris, for example, space was very cramped after Africa, and that was a sensation that physically affected me. It’s possibly why I became interested in those Haussmann façades and the negative shapes in the sky, which seemed to me like a breath of fresh air alongside the rather cumbersome volumes that I didn’t necessarily recognize. And then I painted those Haussmann façades because I found it strange; there was nothing romantic about it.

Yes it does. Okay, it’s certainly possible to find some of these colours in Italy, and in southern Europe, but it’s true that as a general rule my colour range isn’t a northern European one, unless one thinks of Expressionism. When I paint, I try to incorporate these scenes in a reality I’m acquain- ted with. This refers perforce to the Mediterranean area... for example, the mechanical digger comes from a picture taken in Israel. But it’s true, in Africa, blues are perhaps bluer, reds redder, and yellows yellower. In Zimbabwe, for example, the earth is really very red, red-ochre, so you move about over red lands, or yellow lands, and around farms where the ploughed earth is very black, which creates very powerful contrasts.

We can see this contrast in your painting.

Yes. You know, for difficult subjects, colour enables you to introduce a note of hope... And then, in Zimbabwe, as elsewhere, tragedies often occur in places of great beauty. I also think that in painting you always need a contrast, a contradiction between things. So using bright colours to paint dramatic subjects and ruins introduces contradiction.

There, you’re talking about ruins. Could you tell us something about this theme you’ve been developing for three years now, since that famous stay in Israel?

The theme of ruins is not a conceptual choice. Its origins might possibly lie in my interest in deconstructed images, but for me a deconstructed image was a bit too cold. A deconstructed image doesn’t refer to any personal situation, whereas a ruin implies a human story. We can say that

a ruin touches me personally because I see my native land in ruins–the national park, the health system, society, women’s life expectancy, no- wadays around 34-35, and all this in one of the world’s most beautiful countries which, ten years earlier, had the highest life expectancy and the highest literacy rate in Africa... So there you are, the ruins of a society and an identity...

In a way, you contrast this fact, and the horror that exists in many contemporary societies, with the idealism of painting?

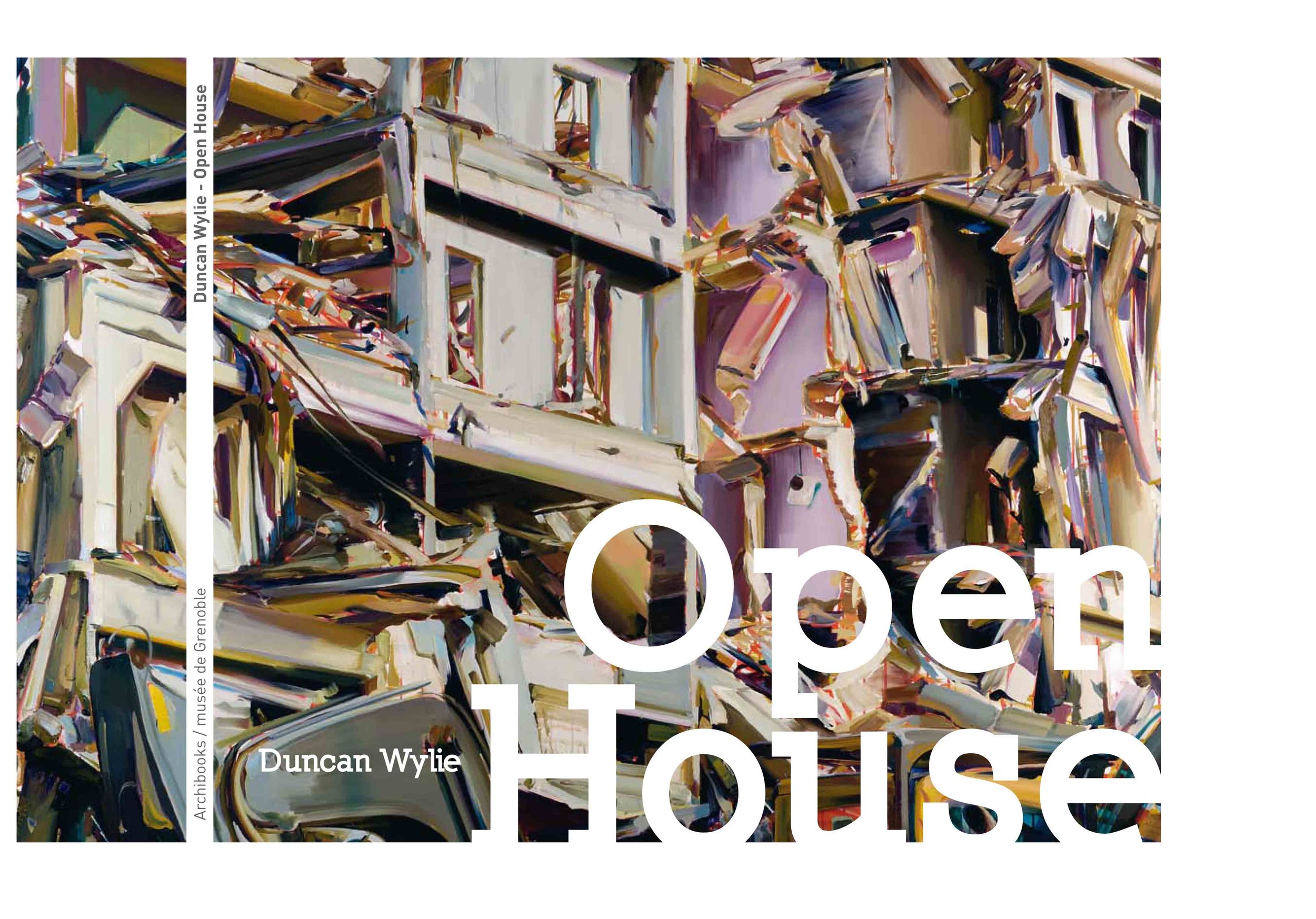

I can convey this with something Gerhard Richter once said, which really struck me: “Art is the highest form of hope”. It struck me ten years ago. It’s not something I’ve always been aware of, but it’s true that I’ve always ma- naged to pull through things thanks to painting. I was in France and had to live off painting. I had to become “naturalized through painting”, and my story is built around painting. The situation in Zimbabwe now touches me personally, in several ways, and I deal with it through painting. This helps me to connect lots of things: my interest in space, in issues to do with rootedness, human problems... this being the case, the choices I make are usually instinctive. And in fact, this theme of ruins encompasses lots of things. For me, for example, the Leipzig façade is almost like Le Boeuf écorché, but I don’t want to sound pretentious, I’m just trying to say that for me it’s a “stripped” façade, laid bare —“flayed” like an écorché.

In another key, with the large picture I’m working on, I’m beginning a little bit to rediscover the space of Hieronymous Bosch, and understand his use

of space, where there are lots of openings, three or four planes, and then openings between the planes. I’d never seen that before. By working on these images, I’m better able to understand how those two artists used space. I’ve never seen the synthetic Cubists quite so clearly as when I pro- duced my very dovetailed, kaleidoscope-like pictures. There’s something a painter friend, Alicia Paz, said about painting and perhaps about a certain Mannerism in contemporary art that I like a lot: “The wild flowers which grow on the ruins of modernism”. I was struck by that image. You’ve got so- mething dead or dying and something else that’s new, fresh, alive, growing right beside it... For me, this paradox is like very lively strokes of paint that enliven an a priori no longer usable structure. Just as when I think of one of my earliest memories in the Louvre looking at a picture by Delacroix which I found rather dull, where there was a dying soldier, sole survivor in a battle scene. Everything was grey and green but behind the soldier’s ear the pain- ter had put some red. That was when I realized that all it took was just a touch of red behind the nails or the ear to give life to that character who was in shadow, and you didn’t know whether he was dead or alive, but, in any event, with that red he made the greens and all the other colours come to life. Without that red, the picture would have had no interest. That’s why, for some years now, when I paint a ruin, instead of using grey and other dusty colours, I choose quite a bright range.

April 2009

Translated by Simon Pleasance & Fronza Woods

Original french text :

Entretien avec Duncan Wylie par Guy Tosatto

Guy Tosatto : Peux-tu décrire le processus d'élaboration de tes tableaux ? Com- ment tu les attaques, ce qui arrive ensuite... ?

Duncan Wylie: En fait, ma démarche est liée non seulement à la manière de travailler la peinture même, d'une manière gestuelle et spontanée–c'est le cas avec le premier petit tableau issu de mon séjour en Israël quand j'ai vu la destruction de Gaza–mais aussi à l'effet visuel de ce tableau où l'on voit distinctement des tuiles qui tombent du toit d'un bungalow. Ce qu'il y a d’important dans cette première petite peinture, c'est que l'on a le sentiment d'un chaos en suspens, avec les tuiles qui tombent, projetées par le bras de la pelleteuse. En fait, en peignant ce ta- bleau, dans un petit format tout d'abord puis en l'agrandissant à un format de deux mètres sur trois, j'ai compris que c'était cette notion d'instantané qui m'interpellait le plus. Un chaos « structuré » ou qui dure dans le temps et qui soit en même temps instantané. Mais à l'époque c'était très instinc- tif, je ne pouvais pas le conceptualiser. Evidemment peindre une trentaine de pelleteuses n'avait pas beaucoup de sens, de plus trouver des clichés qui montrent exactement ce moment-là était très difficile. L’étape suivante fut de trouver comment reproduire « ce moment » par la peinture même. Ça m'a pris du temps et j'ai peint beaucoup de bulldozers, des toiles que personne n'a jamais vues, représentant un moment d'impact, avec une pelleteuse, un bulldozer ou un autre engin, mais toujours avec cette notion d'impact. Et puis un jour, j'ai peint l'intérieur d'une salle de danse avec un toit convexe rouge. Je n'ai pas continué ce travail, mais ce qui m'a intéressé, c'était l'espace vide. Un mois ou deux plus tard, après un séjour à Sofia en Bulgarie, j'ai retourné ce tableau et j'ai vu différemment la structure de cet intérieur avec ses lustres qui pendaient à l'envers. Il y avait un bel espace vide avec des choses qui flottaient et dans cet intérieur, j'ai peint un extérieur complètement éclaté. En faisant cela, j’ai eu le sentiment que les débris que je peignais venaient flotter sur la première image. Je retrouvais ce moment où quelque chose est en suspension... Ce qui m'intéresse aussi, c'est que ce motif de structures éclatées per- met une relation mimétique entre les éléments d'architecture et les tra- ces du pinceau. Tout à coup il y a une indécision entre signe abstrait et forme figurative. Ça, c'est la deuxième clé qui m'a amené là où j'en suis aujourd'hui : peindre une image dans une autre pour qu’elle flotte dans la première. On peut établir un parallèle avec les photographies peintes de Richter où des effets de matière se superposent à une image. Ça renvoie également à mes travaux d'il y a dix ans. De loin, les formes étaient très précises à la manière d'une photographie alors que de près, elles étaient très peintes, avec une touche très affirmée et un rendu presque abstrait. Ce tableau qui s'appelait Paris, Sofia (Harare) parce que peint à Paris d'après les images que j'avais prises à Sofia tout en renvoyant à ce qui se passait au Zimbabwe, était important car il y avait une notion d'échelle très intéressante. En peignant, dans un intérieur, un extérieur a priori plus grand, j'inverse les rapports d'échelle entre ces deux espaces; ce sont des jeux picturaux dont je suis moi seul conscient. Cela rend l'approche un peu surréaliste, et ce jeu me plaît quand je peins. A la fin, on ne voit pas forcément le résultat, mais cette histoire est imbriquée dans l’œuvre. C'est ma manière d'intégrer des choses et de les travailler, sachant qu'à un moment donné elles vont apparaître différemment, dans un an ou deux. J'aime beaucoup Max Ernst, René Magritte et cette notion un peu sur- réelle de flottement qu'on ne voit pas a priori mais qui est présente.

Alors quand je dis superposition d'images, c'est faux, il faudrait plutôt parler d'imbrication d'images.

Non, les deux. En fait, ce système de superposition et d'imbrication me permet de peindre tout le chaos que je veux car c'est le processus pictural qui engendre le chaos lui-même. Cela sous-entend que je peux utiliser des images du réel sans avoir à les reproduire d'une manière littérale. Ce type de reproduction ne m'intéresse pas, parce qu'alors je décris, et si je décris cela signifie que la matière est morte. Ce qui est important, c'est que le processus engendre le chaos, et avec lui on retrouve cette notion « d’une chose qui est en train de se passer ». Ce n'est ni l'avant, ni l'après, c'est vraiment le pendant, c'est le moment même des choix picturaux. Mes images sont très construites, construites par étapes, mais le sort d'une image globale, je ne le contrôle pas du tout. Je peux penser : « tiens, cette image va marcher très bien sur celle-là », et puis au bout du compte une troisième peut venir comme ça, sans crier gare. Avec Power Sharing, j'ai cru que le côté droit du tableau allait être complètement couvert. Mais

l'énergie qui se trouve là est parfaite comme ça avec son aspect très abstrait. Du coup, je dois pousser le côté gauche qui est très photo-réa- liste (sans forcément l'être), pour contrebalancer et donner plus de réalité au côté abstrait. C'est donc toujours un jeu de contraste entre le réel et l'abstrait, cela tient autant de la superposition que de l'imbrication.

Dès tes débuts, tu as travaillé sur le thème de l'architecture, c'est quelque chose qui traverse tout ton travail. Peux-tu en parler ?

L'architecture, oui, ce fut primordial dans le sens où j'ai toujours essayé d'utiliser l'espace en peinture. Et plus il y a d'espace dans la peinture, plus il y a d'espace pour que l'œil se promène. L'architecture, pour moi, c'était nécessaire pour comprendre l'espace dans lequel on vit, dans lequel on travaille. Par exemple à Paris, je trouvais l'espace très réduit après l'Afri- que, c'est une sensation qui physiquement m’a marqué. C'est peut-être pour ça que je me suis intéressé aux façades haussmanniennes et aux découpes négatives dans le ciel, qui me semblaient comme une bouffée d'air à côté des masses assez lourdes que je ne reconnaissais pas forcé- ment. Et puis les façades haussmanniennes, je les peignais parce que je trouvais ça étrange, cela n'avait rien de romantique.

Il y a une chose très frappante dans tes peintures, c'est la couleur. Tu as, disons, une gamme chromatique qui t'est vraiment propre. Est-ce que cela a un lien avec tes origines africaines?

Oui. Bon, bien sûr, on peut trouver certaines de ces couleurs en Italie, ou dans le Sud de l'Europe, mais c'est vrai qu'en général ma gam- me colorée n'est pas celle d'Europe du Nord, à moins qu'on pense à l'Expressionnisme. Quand je peins, j'essaie d'intégrer ces scènes dans une réalité qui m'est connue. Cela renvoie forcément à l'aire mé- diterranéenne... par exemple la pelleteuse vient d'une image prise en Israël. Mais c'est vrai, en Afrique, les bleus sont peut-être plus bleu, les rouges plus rouge, les jaunes plus jaune. Au Zimbabwe par exemple, la terre est vraiment très rouge, plutôt ocre-rouge, donc on se déplace sur des terres rouges, ou jaunes, et autour des fermes la terre cultivée est très noire, ce qui crée de très forts contrastes.

On retrouve ce contraste dans ta peinture.

Oui. Tu sais, pour des sujets difficiles, la couleur permet d'introduire une note d'espoir. Et puis, au Zimbabwe comme ailleurs, ce sont souvent des tragédies qui se passent dans des lieux d’une grande beauté. Je pense aussi qu'en peinture il faut toujours un contraste, une contradiction entre les choses. Alors mettre des couleurs vives pour peindre des sujets dra- matiques ou des ruines, c'est introduire de la contradiction.

Précisément tu parles de ruines, pourrais-tu nous parler de ce thème que tu développes depuis trois ans maintenant, depuis ce fameux séjour en Israël ?

Le thème de la ruine, ce n'est pas un choix conceptuel. On peut peut-être en trouver l'origine dans mon intérêt pour les images déconstruites, mais pour moi une image déconstruite était un peu trop froide. Une image dé- construite ça ne renvoie à aucune situation personnelle, alors que la ruine implique une histoire humaine. La ruine, on peut dire que ça me touche personnellement parce que je vois mon pays natal en ruine, le parc national, le système de santé, la société, l'espérance de vie des femmes qui est aujourd'hui autour de 34-35 ans, et tout cela dans un des plus beaux pays du monde qui avait, il y a dix ans, la plus haute espérance de vie et le plus haut taux d'alphabétisation en Afrique... Donc voilà, c'est la ruine d'une société, d'une identité...

A ce constat, face à l'horreur dans nombre de sociétés contemporaines, toi tu opposes, d'une certaine façon, l'idéalisme de la peinture?

Je peux traduire cela avec l'une des phrases de Gerhard Richter qui m'a le plus marqué «L'art est la plus haute forme de l'espoir». Ça m'a marqué il y a dix ans, ce n'est pas quelque chose dont j'ai toujours eu conscience mais c'est vrai que je m'en suis toujours sorti grâce à la peinture. J'étais en France, il fallait que je vive de la peinture, il a fallu que je me fasse « naturaliser par la peinture » et mon histoire se construit autour de la peinture. Et puis cette situation au Zimbabwe maintenant me touche personnellement, de plusieurs façons, et je me confronte à cette situation par la peinture. Cela me permet de lier beaucoup de cho- ses: mon intérêt pour l'espace, pour les questions d'enracinement, de problèmes humains... Cela étant, en général chez moi ce sont des choix instinctifs. Et de fait, ce thème de la ruine englobe beaucoup de cho- ses. Par exemple pour moi la façade de Leipzig, c'est presque comme Le Bœuf écorché, enfin sans vouloir être présomptueux, mais pour moi c'est une façade écorchée, c'est un écorché.

Dans un autre registre, avec le grand tableau en cours, je commence à retrouver un petit peu l'espace de Hieronymus Bosch, à comprendre son utilisation de l'espace, un espace où il y a beaucoup de percées. Il y a trois ou quatre plans et puis des percées entre les plans. Je n'avais jamais vu ça auparavant. En travaillant sur ces images, ça me permet de mieux comprendre comment ces deux artistes ont utilisé l'espace. Je n'ai jamais mieux perçu les cubistes synthétiques que lorsque je faisais mes tableaux très imbriqués façon kaléidoscope. Il y a une phrase d'une amie peintre, Alicia Paz, à propos de la peinture et peut-être d’un certain maniérisme dans l'art contemporain, qui m'a beaucoup plu: «comme des petites fleurs sauvages qui poussent dans les décombres de la représentation ». L'image m'a marqué. Tu as quelque chose de moribond et quelque chose d'autre de neuf, de frais, de vivant, pousse juste à côté... Ce paradoxe pour moi est à l'image de traits de peinture très vifs qui réaniment une structure qui n’est a priori plus utilisable. De la même manière, lorsque je pense à l'un de mes premiers souvenirs au Louvre devant un tableau de Delacroix que je trouvais assez terne, où l'on voyait un soldat mourant, ou seul survivant dans une scène de bataille, tout était gris et vert mais le peintre avait placé du rouge derrière l'oreille du soldat. J'ai compris alors qu'il suffisait juste d'une touche de rouge derrière les ongles ou derrière l'oreille pour donner de la vie à ce personnage qui était dans l'ombre, dont on ignorait s'il était mort ou vivant, mais qui en tout cas avec ce rouge faisait exister les verts et toutes les autres couleurs. Sans ce rouge, le tableau n'aurait eu aucun intérêt. Voilà, c'est pourquoi depuis quelques années, lorsque je peins une ruine, au lieu de prendre du gris ou des cou- leurs poussiéreuses, je choisis une gamme assez vivante.

Avril 2009